The initial shock has given way to a double horror. First, there is the inescapable fact that more than 62 million Americans voted for this man. Most white college graduates preferred him. Most white women preferred him. Presumably, many of those 62 million are not bigots, bullies, sexual predators, or compulsive liars. But they knowingly voted for someone who is all of those things and more. Then there are the horrific practical implications. During the campaign, the novelist Adam Haslett observed that “the endless acts of verbal violence shock us, render us so passive and stunned that we no longer recognize the horror of what we are living.” But that is nothing compared to the exhaustion of the horror that awaits us under the Trump administration. His election—along with Republican control of both houses of Congress and more than two-thirds of state legislatures—would likely precipitate an assault on civil rights, civil liberties, environmental protection (including a rollback of early, tentative steps to address global climate change), consumer protection, reproductive rights, gay rights, workers’ rights, prisoners’ rights, humane immigration policies, assistance to the poor, gun control, anti-militarism, support for public education, and so on. It would be bad enough for anyone deeply committed to any of these issues; for those who care about all of them, it would be hard to comprehend, let alone become angry about, and become active in opposing a tidal wave of reactionary policies that is likely to continue daily for years to come.

The potential impact on official policy is staggering. Yet I can’t help thinking about the man himself.

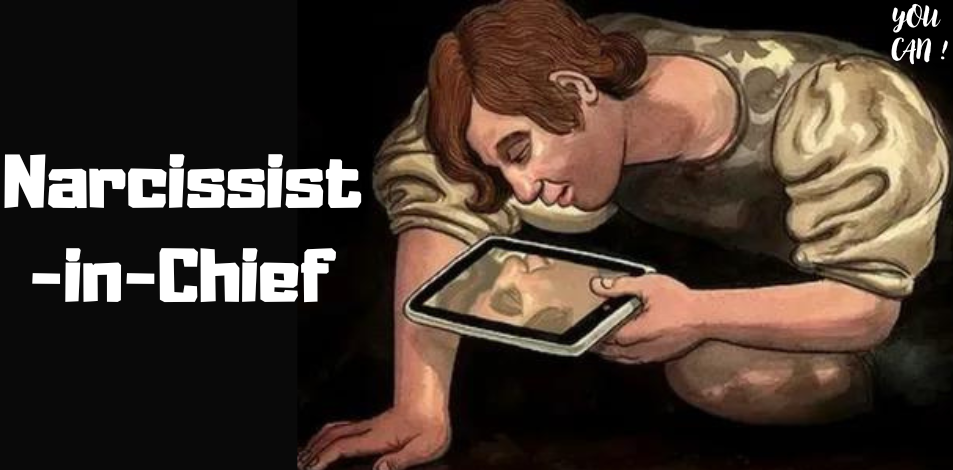

Throughout the campaign, I found myself viewing Trump’s behavior through a psychological lens, not only disturbed by the aggressive racist remarks about Mexicans or Muslims but also fascinated by the deeply damaged human being who was saying these things. Even before he ran for president, Trump was the first proof of the axiom that it is possible to be rich and famous without being a successful person, psychologically or morally. Explaining the details now that we are more familiar with him is adding a layer of disbelief and amazement to the fact that so many people voted for him anyway. This psychological perspective is also crucial to trying to predict how much damage he will do to the country and the world, especially to the most vulnerable.

Donald Trump has been characterized as someone who:

- is prone to boasting, bragging, and ostentatiousness to the point of self-mockery;

- is not only thin-skinned and whiny but vindictive when provoked or even criticized;

- is restless, with the attention span of a toddler;

- is desperately competitive, driven by a categorization of the world into winners and losers, and sees other people (or countries) primarily as rivals to be overcome;

- is surprisingly lacking not only in knowledge but also in curiosity;

- is not only habitually uttering blatant lies on a fairly constant basis but seems unaware of how untruthful he is, as if the fact that he believes or says something makes it true; and

- has a sense of absolute entitlement—so that if he wants to kiss or hold an attractive woman, for example, he should of course be free to do so—along with a lack of shame, humility, empathy, or the capacity for self-reflection and self-examination.

Even if you start thinking about different kinds of flaws, you come back to psychological issues. It’s not just that he’s ignorant or even uncurious; he seems incapable of admitting that there’s something he doesn’t know. It’s not just that he lacks the cognitive means to see himself as others see him (or to reflect on his failures), but that his psychological makeup doesn’t allow him to stop and think about who he is; he’s like a shark, a blind eating machine that must always move forward or die. Similarly, while his speech rarely goes beyond elementary school vocabulary or grammar, what’s more troubling than his cognitive limitations is his egocentrism. A close analysis found that he’s not only prone to monosyllables but also to megalomania: the one word he uses more than any other is “I”—and his fourth favorite is his name. Donald Trump seems to me a prime example of how a lifelong campaign of self-congratulation and self-aggrandizement (acquiring as much as possible and then slapping his name on everything he owns) is an attempt to compensate for a deeply rooted insecurity. He fears that he is worthless, worthless. His quest for humiliation and conquest, for possession and ostentation, may indeed be strategies for proving to himself that he exists, reflecting what R. D. Laing called “existential insecurity” (in a chapter of the same name in his classic book, The Divided Self). But why did Trump praise Putin? He explained that it was because Putin “said nice things about him.” The whole spectacle of his party’s convention was a $60 million attempt to prove that he was popular. If you watch the man carefully, before he attacks a critic, before he unleashes blind rage, insults, and threats, you will find yourself in a moment of genuine bewilderment and pain that anyone could say something about him that is not his. Indeed, his weakness and naked need would almost make us pity him were it not for the potentially disastrous consequences when someone with this quality comes to a position of power.